MEMBERS SHOULD LOG IN FIRST TO ACCESS FULL ARTICLES

|

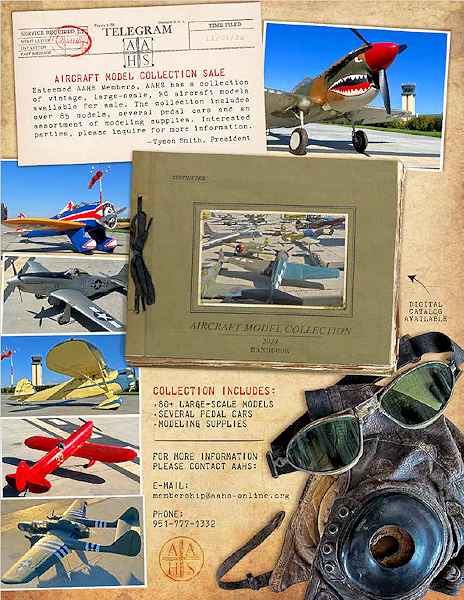

The AAHS has a collection of vintage, large-scale, aircraft models available for sale. The collection includes over 80 models, several pedal cars and an assortment of modeling supplies. |

|

|

Barnstorming with a Blimp; The Cruise of the "Wonder Ship"NC900SH Editor’s Note: At one time or another many of us have looked up into the night above the leading cities of the nation and seen a flashing light slowly edging its way across the sky, accompanied by the low monotonous drone of engines. As this phenomenon drew closer one may have been startled to see a flying red horse, complete with flapping wings, or a giant whale swishing its tail, or perhaps a great flamingo winging its way through the darkness. Sights such as these have captured the imagination of millions of people around the country and given a great deal of pleasure to youngsters. They have even had some humorous side effects. One gentleman, upon leaving a bar in the Santa Monica area, looked up and saw the famous red horse-and promptly took the pledge. Former AAHS member Bob LoVece had a very large and interesting part in the cruise of the “WONDER SHIP.” He was persuaded to set down his account for the Journal, told herewith. |

|

|

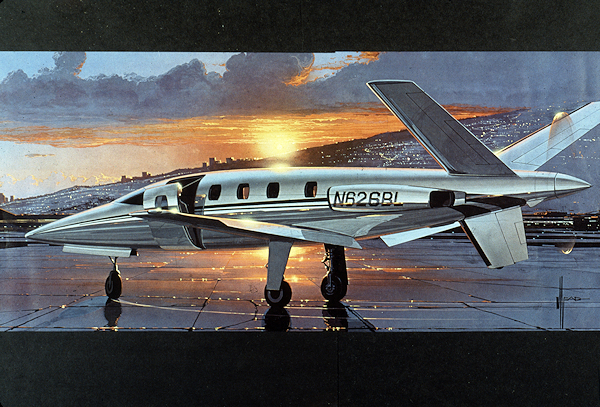

December 32, 1980: Perseverance, Lear Fan Style In a rather dramatic rescue, the Museum of Flight in Seattle acquired the Number 1 Lear Fan prototype for display. A true rescue it is, because the airplane would have gone to NASA for use as a structural test article, resulting in its destruction. A total of $40,000 was raised through donations to secure that revered piece of history, which now hangs in the museum’s Great Gallery. |

|

|

After our mom’s death, my sister and I spent some time preparing the "old homestead" for sale. Imagine my surprise when I discovered in a dark corner of the attic all of my old stuff – including lots of childhood treasures I thought had long since been consigned to the landfill. There were baseball cards, comic books, and an old wooden box that my dad had made, containing a heap of my toys, many of which were aviation related. Most of the airplanes were smaller and more beat-up than I remembered them, but there they were. |

|

|

Mitchel Airfield: Long Island’s Forgotten Air Force Base Students changing buildings at Hofstra University and Nassau Community College on Long Island are most likely oblivious to the fact that they are walking on areas that were once occupied by taxiways and runways. To which airport they belonged is either equally elusive to determine or altogether forgotten. But the two hangars which are now part of the nearby Cradle of Aviation Museum and house some 70 historic aircraft, may provide a clue. “Mitchel Field,” they indicate. But where exactly did this “field” go?

Early Area History

Military in purpose, Mitchel Field was located in an area originally designated the "Hempstead Plains" and became the latest in a line of such military installations.

"Most of the aviation activities on Long Island centered around the skies of the Hempstead Plains,” according to Reggie Shore in his article, “Mitchel Field and the History of Aviation on Long Island". The Hempstead Plains, a 60,000-acre area in the center of Nassau County, is the easternmost native grassland in North America and somewhat of a mystery because it cannot be explained by its geological foundation. |

|

|

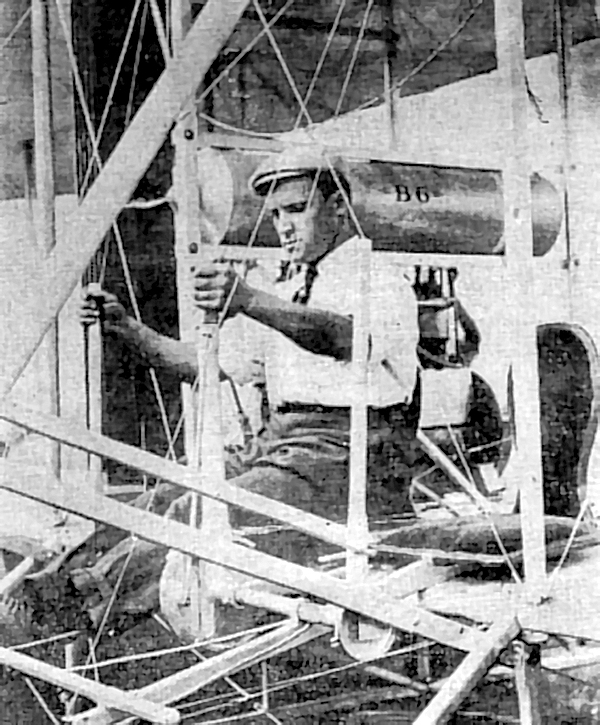

Arthur L. "Al" Welsh; Early Wright Exhibition and Test Pilot Laibel Wellcher was born in Kiev, Ukraone, then a part of Russia, August 14, 1881. He was one of a large family that immigrated to the United States in 1890 when he was nine years old. They eventually ending up living in the Washington, D.C., area. Willcher received his elementary education from a retired teacher who lived with the family, and was particularly adept at mathematics, languages, and pen and pencil etching. Athletically inclined, he learned to be an expert swimmer and oarsman. He became a naturalized citizen. Training Later that year the Wrights decided to go into the exhibition business to demonstrate and promote their aircraft. They hired renowned balloon and dirigible man, Roy Knabenshue, to become their exhibition manager and run the program. Knabenshue was well versed in the necessary procedures and problems involved in carrying on such activities. They needed . . . |

|

|

World War II Interned and Captured Aircraft from the collection of Hans-Heiri Stapfer The Society recently received a contribution from a Swiss individual, Hans-Heiri Stapfer, of a collection of WWII photos. They fall into three categories. American manufactured aircraft captured and operated by the Axis (mostly Germany), U.S. aircraft Interned by the Swiss after landing or crashing on Swiss territory, and Russian Air Force operation of Allied aircraft (mostly P-39 and B-25s). The following is an sample of this collection with details known about each individual aircraft. Aircraft Interned by Swiss On February 22, 1945, 2nd Lt. Robert Rhodes was flying North American P-51B-15-NA, 43-24853, code VF-U, "Little Ambassador" on a bomber escort mission to Ulm, Germany. He was Assigned to the 5 Fighter Squadron, 52 Fighter Group, 15 Air Force, operating from Madna, Italy, at the time. There are conflicting reports as to what caused the situation leading up to Rhodes ditching the plane in the Rhine River near the Swiss town of Buchs. One source states his plane was damaged by anti-aircraft fire, a second claims it received damage in a "fierce dog-fight." Either way, Rhodes realized there was no hope of getting the damaged plane back to Italy and ditched it. |

|

|

The Stearmans of Brevard County Florida As the world-wide efforts of WWII progressed towards its ultimate conclusion a dilemma of what to do with a gigantic supply of surplus military equipment arose. The U.S. Government faced the immense problem concerning the disposal of surplus military equipment and real estate in such a magnitude as no country had ever before experienced. |

|

|

What the Heck is Going On Here? A Two-Seat Lockheed F-4 Conversion In early 2023, while conducting research in Records Group 18 (RG18) relating to the Curtiss O-52 Owl at the National Archives at College Park, Maryland, I came across a rather thick file labeled simply "Photographic Aircraft," which had apparently been misfiled amongst four equally stout folders specifically labeled "Observation Aircraft." |

|

|

This issue of the Forum focuses on contributions from a number of members focusing on broad spectrum of subjects, many at recent events.

The Society has thousands of images in need of cataloging. You can help by volunteering to assist in cataloging from your own home. Interested in helping? Go to

www.AAHSPlaneSpotter.com and check the system out. |

|

|

The readers of the AAHS Journal enjoy the talents of many engaging authors that, with their research and writing, give us fascinating insights into the development and use of aviation here in these United States. The depth and breadth of aviation topics brought to life in the AAHS Journal’s pages is a stunning testament to the enduring interest that aviation holds in our culture. It would be hard to find another publication that routinely speaks to such diverse topics as the use of material substitutes in aircraft production, women’s aviation fashion, aviation toy collections, and how commercial airline routes were developed. Jerri Bergen |

|

American Aviation Historical Society

American Aviation Historical Society