MEMBERS SHOULD LOG IN FIRST TO ACCESS FULL ARTICLES

|

Excerpts from

|

||||||

|

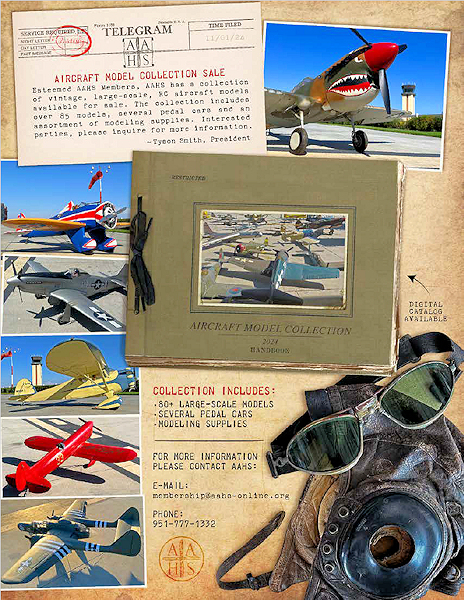

The AAHS has a collection of vintage, large-scale, aircraft models available for sale. The collection includes over 80 models, several pedal cars and an assortment of modeling supplies. |

|

|

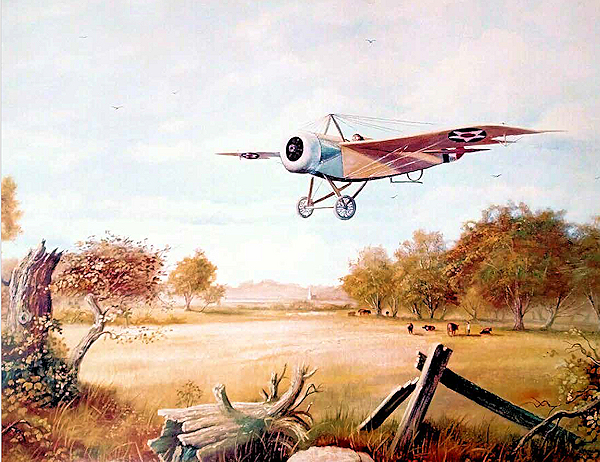

The Albree Pigeon Fraser: The First American Pursuit

Most people who know about American aviation during the WWI are aware that the U.S. Army Air Service had to rely on its foreign allies for combat aircraft to fight the Germans Jagdgstaffels over the Western Front. This did not stop American manufacturers from attempting to fulfill the U.S. military’s need for combat-capable aircraft. Yet the first monoplane design to win a U.S. military contract for a fighter was fated to become an oddity barely remembered by a few aviation historians. This is the story of the Albree Pigeon-Fraser. |

|

|

TThe Strange Case of the Burning Junkers

It has always been a mystery why one of the great aircraft of history, the Junkers F13, turned out to be an utter disaster in the United States - and only here. So much so that it is hardly remembered at all - even though, for exactly two years, it was a major embarrassment for many prominent people. Herr Junkers defies Convention During and after the Great War, Professor, Dr. Hugo Junkers had a big factory in Dessau, about 50 miles southwest of Berlin. Dessau was then the small but glorious capital of the Freistaat Anhalt and is now in Sachsen-Anhalt. Both the town and the sprawling Junkerswerke west of it were bombed flat during the war. There is a new museum there now, replacing the famous Junkers exhibit Colonel Lindbergh visited in 1938. Lindbergh, now with the U.S. Army, returned to the rubble in June 1945, just ahead of the Soviets, and seized the priceless technical library Hugo Junkers had spent a lifetime assembling. It has never been found again.[1] |

|

|

Coast-to-Coast and Back Again in a JL-6

A remarkable event in the history of aviation took place in the summer of 1920. One expedition notched two records: the first coast-to-coast U.S. airmail delivery and the first round-trip transcontinental passenger flight. To do this, three airplanes left New York City, following a great circle path to San Francisco. |

|

|

Roosevelt Field: Once the World’s Premier Airport

Mention the name "Roosevelt Field" to a Long Islander and he will most likely conjure up images of sales in Macys department store, the set of golf clubs he has been eying in Dick s Sporting Goods, and lunch in the food court. But a plaque entitled "Historic New York Roosevelt Field" indicates that there was once another "Roosevelt Field" here, stating, in part, that "the level, treeless Hempstead Plains - a unique Long Island attraction since colonial days - was ideally suited for flying fields. Glenn Curtiss made the first flight here in 1909 in his ’Gold Bug,’ which resembled an enlarged box kite." Airfield Origins Like trees that ultimately spring from flat fields, the airport itself rose from one that was originally called the "Hampstead Plains."

"The central area of Nassau County, known as the Hempstead Plains, (was) the only natural prairie east of the Allegheny Mountains," according to Joshua Stoff in Historic Aircraft and Spacecraft of the Cradle of Aviation Museum (Dover Publications, 2001, p. viii). "Treeless and flat, with only the tall grasses and scattered farmhouse, this area proved to be an ideal flying field and was the scene of intense aviation activity for over 50 years." The first brush stroke was thus applied. |

|

|

The Thomas Brothers; The Thomas brothers pioneer aviation biographies should be recorded jointly because their early aviation engineering and plane building accomplishments were made as a team. |

|

|

A History of Randolph Air Force Base

In April 1960, my father drove my mother, brother, grandparents, and me from North Texas to San Antonio for a visit. On the outskirts of San Antonio, which was farmland in 1960, we took a detour to Randolph AFB. I didn’t know what to expect, but as we crossed the railroad tracks and entered through the main gate, there in the distance was a building like I had never seen before on an Air Force base. The building, nicknamed "The Taj Majal," was tall, white, and served as the headquarters building for the base. Having grown up near air bases that were built virtually overnight during World War II, I had never been on a base with permanent buildings. I immediately fell in love with Randolph. Later, when in the Air Force, I was assigned there twice, 1970-1973 and 1977-1981. I retired in 1991 and returned to Universal City, which was right across the railroad tracks from Randolph. I continued my love affair with Randolph and this article is the culmination of this infatuation. On a flat tract of former farmland about 17 miles northeast of downtown San Antonio, Tex., the Army Corps of Engineers, in its biggest project since the Panama Canal, built in fewer than three years a permanent airfield that resembled a Spanish village. That project was originally named Randolph Field, until 1948, when it became Randolph Air Force Base. By the mid-1930s, Randolph Field’s fame had spread and it was known as "The West Point of the Air" for the Army Air Corps. Today, because of its architectural beauty, Joint Base San Antonio - Randolph is "The Showplace of the Air Force." Genesis Randolph’s roots were planted in controversy. After the loss of the Navy’s rigid dirigible USS Shenandoah in 1925, outspoken Air Service Colonel William "Billy" Mitchell accused Army and Navy leadership of "almost treasonable administration of the national defense." Mitchell was already a thorn in the side of President Calvin Coolidge, so he ordered the colonel to be court-martialed. Mitchell used the trial as a sounding board for championing military aviation and criticizing military leadership. He was convicted and sentenced to suspension for five years without pay, which Coolidge later adjusted to half-pay. Mitchell resigned instead.[1] |

|

|

Spring 2025, Vol. 70, No. 1 - The PBY’s of the Kendall Family

[While we strive for accuracy in our publications, to a large degree we rely on the authors to have thoroughly research their topics. Even then, we all sometimes get it wrong. The AAHS has always published corrections and updates to articles when new information (or corrections) come to light. Therefore, we appreciate the time and effort taken when someone brings this information to our attention. The following is a response from David Legg, of the Catalina Society and editor of the "Catalina News". We are grateful that he has taken the time to point to errors and provide update information for this story.] I have just had the opportunity of seeing Jerri Bergen’s article The PBY’s of the Kendall Family in the Spring 2025 edition of the AAHS Journal. There was some very good background information in the article that went beyond the "nuts and bolts" data. In particular, I appreciated the very interesting coverage of the background to the Kendall family and the use of PBY-5A N5590V in the Pacific during the 1960s. |

|

|

It has been an eventful few months here - assisting Flabob Airport in the celebration of their 100th anniversary (see FL 25-2 for more details), book sales at local air shows, meeting new volunteers at the Riverside Aviation Expo, and more recently planning on some additional space at AAHS (see Spring Journal CEO message). |

|

American Aviation Historical Society

American Aviation Historical Society